The Game of Jenga: How the Theory of Facial Expressions Tees on the Verge of Collapse

- Por Alan Crawley

- En English

- 2 comentarios

1. Introduction

This title is not just sensationlaist, it’s an attack to your intellectual complacency. I know it will attract attention for the same reason it will spark annoyance: the theory of universal facial expressions of basic emotions (BET) is today accepted as if it were a religion. It professes that the face is the main vehicle of emotions, that the facial muscles move in the same way in all members of the homo sapiens species and that certain emotions are expressed on the face in the form of fixed expressions. But are its postulates true? Follow me in this controversial edgy fight against the heavyweight champion of facial expression theories.

In this article I will try to offer an updated perspective on the science of facial expression. I will use religion as an analogy. To do so, I will be guided by the definition that religions are ideologies with their own belief systems. This religion of the facial expression of emotions, instead of ethics and morals, proposes rules and norms about its functioning, behavioral predictions, descriptions of its evolutionary purpose and universal criteria. Let’s dive into the gospel of facial expressions of basic emotions.

Of course, it is not true that everyone adheres to BET as a religion, although its popularity among its believers is undeniable. There’s no church with more acolites by a huge number of members. Furthermore, no one wants to hear that they pray to the wrong God, so before judging my words I ask that you give me the opportunity to explain in detail the numerous problems with this theory. If you are not open to changing your mind, please go ahead and close this tab and grab another of Ekman’s texts.

2. Why do I write this article?

I recently came across a statement that I believe is disconnected from the current state of the science of facial expression. It was presented as an absolutely unquestionable truth, which, in itself, is strange in the scientific field. This argument was also put forward by a renowned international reference in the field of Nonverbal Communication, which is why it initially caught my attention. I clarify here, before starting, that I decided to keep the name of the researcher anonymous. Since his words were in the public domain rather than in a scientific article, my response will replicate that. Let’s see what he said.

Images of the six basic emotions initially proposed and later discovered by Dr. Paul Ekman. Top from left: anger, fear and disgust. Below: surprise, joy and sadness

His statement was a forceful defense of the BET, which assumes that there are six or seven universal facial expressions, one for each emotion (happiness, sadness, fear, anger, surprise, disgust and contempt). Each of them has, according to an important part of the accumulated evidence, a prototypical facial expression that makes it visible to its peers. It doesn’t matter sex, race, gender or culture, everyone makes the same expressions or at least that’s what is presumed.

During an interview this researcher made the following challenge:

“I challenge anyone to show me a situation in which an intense emotion is aroused in someone, and we know that it is intense, that there is no doubt that it has been aroused in that person, and that there is no reason to hide it or – simply that it has been raised. And there, that expression does not occur.

Show me that study. Does not exist. Show me a blind individual, who, in that situation, whose facial muscles can move, because some individuals cannot move those muscles, and strong emotions are aroused in them. Their faces will move the same. Show me the study (in) that raises the emotion and that expression does not happen. You won’t find that” (bold mine).

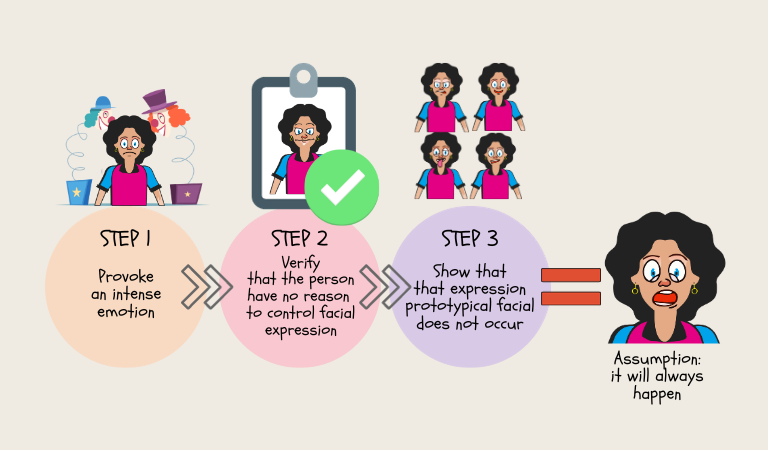

To simplify it a bit, I leave you a brief summary of the challenge:

1- Provoke an intense emotion (and that we all know that it is intense)

2- That the person has no reason to hide / regulate facial expression

3- Demonstrate that this prototypical facial expression does not occur

3. Four reasons to reply to the challenge

First and foremost, the challenging tone caught my attention like a moth to the light. This is uncommon in the realm of academics, so I felt compelled to scrutinize it. This isn’t just a scholarly challenge; it’s a gladiator battle in the arena of scientific integrity.

Second, I felt like I recognized an almost identical statement, but with a slight difference: it was published almost 40 years ago, before the invention of the first laptop computer. In 1980, Paul Ekman stated that “when someone feels an emotion and is not trying to conceal it, their face looks the same no matter who that person is or where they come from” (p. 7). Isn’t that a bit too simple?

Thirdly, I can point to four concrete scientific articles that can shatter the illusion of robustness behind BET theory. I am not even exhaustive, I’ll do this just for fun.

For instance, studies by Camras and colleagues (2017) demonstrated that the correlation between facial expressions and fear is moderate, both in infants and children. In other words, feeling fear sometimes produces the supposed facial expression stipulated by BET. Okay. But, among their argments, they included that the supposed prototypical emotional expressions of the face do not seem to be commonplace, even in situations that elicit an emotion with evident intensity. They acknowledged that “negative emotional facial expressions of full face were infrequent” (p. 293). This is a significant blow to the theory. Let’s dig deeper.

The second study is perhaps the most amusing, with results that are somewhat challenging for universalists. German researchers Achim Schützwohl and Rainer Reisenzein (2012) conducted a study in which participants entered a room after crossing a hallway. Inside, they completed a questionnaire and, upon exiting through the same door they entered, found that the hallway had become a new room with green walls and a red office chair in the center. Participants were filmed and later interviewed. Here’s the result: only 5% of the participants displayed the complete prototypical surprised face, even though almost everyone claimed to feel surprised. Ouch. Was the emotion not intense enough?

In a third study composed of seven different experiments (Reisenzein et al., 2006), participants’ facial expressiveness was recorded while they were induced with stimuli to feel surprise. Only 1% exhibited the facial movements proposed by BET. What may be even more unexpected is that “the ‘complete’ surprised face was never seen,” despite the majority of participants reporting feeling surprised. Even a broken clock is correct twice a day.

In the aforementioned studies, people reacted by moving their faces in many different ways and rarely used the expected facial expression according to the BET model. Let’s suppose for a moment that in each research, the induced emotion’s intensity was not intense enough to trigger the genetic program with the prototypical expression of surprise or fear. Would that resolve the wide diversity and lack of prototypicality of the expected expression? Personally, I don’t think so, but what about you?

Let’s present the jury a robust evidence: Prototypical expressions are infrequent. I believe there is agreement among the majority of facial expression researchers on this point (as opposed to researchers in the field of emotions, see Ekman, 2016). The esquematic predicted facial expressions are far less frequent than predicted. The above doesn’t negate that such prototypical emotional faces (those proposed by BET) may appear in both unfamiliar and familiar faces with some recurrence, demonstrating a degree of universality (especially for joy). This should be considered. However, there is an immense difference between an assertion that says “prototypical expressions occur infrequently” and, in opposition, one that says “the prototypical expression will always occur” (unless there are reasons to regulate expressiveness).

Before mentioning the fourth article, I want to acknowledge that there are other scientific publications that challenge the traditional paradigm of universal facial expression. These studies address diverse topics, such as Duchenne smiles (misnamed ‘genuine’ smiles) in negatively valued situations (Harris & Alvarado, 2005), the ambiguity of pain and pleasure expressions (Fernandez-Dols et al., 2011), difficulty recognizing intense emotions during triumph and defeat solely from the face (Aviezer et al., 2012), or after receiving good or bad news (Wenzler et al., 2016). Each of these findings offers evidence that deserves deeper examination if we want to understand the complexity of human facial expressiveness more comprehensively rather than get stuck in a simplified catelog of platonic expressions.

The fourth study defies BET, by Durán and colleagues (2021). I believe it will be remembered for its significant contribution to this debate that has been going on for over a century (Gendron & Barrett, 2017). It is a study of studies, a so-called meta-analysis. In this study, after processing 55 articles reporting 69 studies, it was found that the relationship between proposed universal facial expressions and internal experience reveals a weak or moderate correlation. Only 6% to 27% of the 3,847 participants displayed the complete prototypical expressions of basic emotions.

Although this relationship falls within the expected parameters for social sciences, it is incongruent with BET propositions and with the challenge that motivated this article. The evidence of the last 30 years consistently demonstrates the fragility and imprecision of the predictions stipulated by this dogmatic theory, which is undoubtedly the most prayed to date.

The results of the four previous studies indicate a weaker and more complex relationship between facial expression and emotion that the simplified prediction of BET. This discovery aligns with the current inability to distinguish pathognomonic signals (the “signature”) in physiology and areas of the brain for each basic emotion (although some have been proposed, there is a consensus that there is a lot of physiological and cerebral variability rather than prototipicity).

Four of the most powerful and frequent arguments of the BET theory. From left to right, studies with: 1) infants, 2) non-human primates, 3) congenitally blind and 4) different cultures

Currently, universalists often dismiss these studies, referring to their own data, but without addressing the counterarguments (I am generalizing). In other words, instead of clarifying the results that contradict BET, they rely on the evidence in its favor. On the other side of the debate, and here I believe the researcher who issued the challenge is correct, critics generally do not offer viable explanations for all the arguments supporting BET.

Some of the most solid arguments frequently put forth in favor are the results of studies on facial expression 1) in newborn babies, 2) in non-human primates, and 3) in deaf-blind individuals (cross-cultural studies are also cited, although current evidence partially questions this argument).

Regarding the previous three arguments in defense of BET, I believe there is existing evidence to question the validity of the first two – new borns and non-humans – (Camras et al., 2010; Gaspar et al., 2014), while studies of facial expressions of emotion in congenitally blind individuals support BET (Galati et al., 2003). Particularly, a review study found that in 15 of 21 studies, the universality of facial activity in the blind was supported (Valente et al., 2017).

I believe that the diversity of results, both in favor and against different theories, cannot yet be explained. It seems that the face is much more complex than expected. Could it be that we still don’t fully understand facial expressiveness? Is it wrong to aknowledgede it? Blindly sitcking to BET echoes the similarity between stubbornly using a typewriter in the age of smartphones.

To make matters more complicated, in fourth place, I seemed to identify two aspects in such a challenge that, at first glance, seem impossible to satisfy. This leads me to the simple conclusion, in my opinion, the proposal cannot be scientifically investigated. Essentially, the challenge, while well-intentioned, is impossible to test (given current conditions). Moreover, one could argue that such a study is not even the answer to understanding what the face communicates because it puts emotions as the center of the universe of internal states, which is a (bad) habit. Let’s leave the geocentric model behind (emotions in the center) and build upon creating a more adequate heliocentric model in the field of nonverbal communication. We need a copernican gyre.

Before providing a detailed explanation of why I believe this experimental challenge cannot be carried out, I want to clarify something. Currently, there is a plethora of theories about facial expression. Authors like Scherer, Fridlund, Russell, Barrett, Scarantino, Glazer, to name a few, have proposed different explanations regarding the relationship between facial actions and internal experiences or intentions. It must also be recognized that even followers of Ekman, Dacher Keltner and Alan Cowen (Keltner et al., 2019), have already acknowledged that the relationship between the subjective experience of an emotion and facial expression is more modest than BET claimed. The same is true for Linda Camras (2017), a student of Ekman. It’s not a dichotomy neither simple.

Having said that, let’s delve into the challenge

4. Impossibility of carrying out the challenge.

1) Imprecision of "emotion" measurements

How do we know when an emotion is ‘activated’? The evidence to date has not provided a categorical answer. For example, in thousands of studies, participants have been asked to complete a form about their emotions before, during, or after a specific event. To this day, this remains the most widely used measurement for assessing emotions. However, it is known that self-report is a rather imperfect measurement for detecting the presence or absence of emotions (Barrett et al., 2020). In the words of Caroline Keating from Colgate University, “what people say they feel is no guarantee of how they actually feel” (2016). It is a useful method that contributes to the advancement of science, but its shortcomings must be acknowledged.

Perhaps some readers might suggest physiological measurements as an alternative, such as changes in heart rate, skin conductance, or respiration, to name the most important ones.

However, the evidence points to the absence of a distinct physiological fingerprint or distinctive pattern for each basic emotion (For a more comprehensive analysis, see Barrett, 2017). Data collected from four meta-analyses concluded that there is no evidence of a unique ‘signature’ or ‘fingerprint’ for each basic emotion; instead, each emotion can produce a symphony of different physiological changes. For example, under the experience of fear, blood pressure can increase or decrease depending on various factors.

Lastly, someone might suggest facial expression as evidence of emotion. In some cases, it must be undeniable that the face reflects a strong emotional experience, but is it sufficient as proof of emotion? In fact, meta-analytic studies show a discouraging trend that the correlation between felt emotion and facial expression relatively low-moderate (Duran & Fernandez-Dols, 2021). When a person reports feeling the expected basic emotion, their facial movements do not correspond to the facial expression stipulated by BET in the majority of cases. In other words, there is a correlation between the two, but this link is weak.

What’s even more difficult to justify for BET adherents is that some studies even show that in situations where a person should evidently feel the emotion (like the first three studies mentioned above), the ‘prototypical’ expressions are conspicuously absent.

The parallel to platonic idealism becomes inescapable: in the lab, you can ask students and actors to pose those facial expressions, but in the real world, we are yet to find these ideal expressions.

From all of this, something important emerges: there is currently no objective measurement of the presence of an emotion (Barrett et al., 2020). Simple and disappointing, but realistic. This argument is very powerful because it attacks the very essence of the BET theory. If none of the available measures reliably indicate the experience of a particular emotion, how can universalist researchers know that a particular facial expression occurs when an emotion is felt?

Let’s take an example that might be relevant to millions of people daily. Even though one can perceive and interpret based on a facial expression that one’s partner is angry, it doesn’t mean it can be scientifically proven. How many times we think we are right but it is just an illusion no more than an mirage in the desert. This is no small limitation and questions the cornerstone of emotional theories about facial expressiveness: How are emotions measured?

Along the samelines, how can one be so sure of emotional activation when not only a precise definition is lacking, but also scientific methods to validate them are missing? It’s complex, and perhaps it’s enough evidence to be a bit more skeptical rather than shouting to the winds with ceratinty that we cracked the code of emotional facial expression.

But I don’t want to be overly pessimistic. Some might think that by questioning every detail, the intention is to discredit a theory by nitpicking. While it may seem that way, I hope to demonstrate that each critique is aimed at getting a little closer to the most objective “truth” possible, one that aligns with accumulated evidence. It’s not about being right or attacking others, but rather about analyzing the veracity of the statements and foundations of BET in depth. I have no horse in this race. Instead, I advocate for finding the best explanations for our science.

Suppose for a moment that these measurements -self-report, physiology, and facial expression – offer a degree of (imprecise) reliability and validity. Even if we accept this premise and use these criteria to carry out the researcher’s challenge, another insurmountable weakness must be addressed before facing what the researcher has proposed.

2) Experimentally unviable situation

The Achilles point of the proposed challenge is the requirement for a situation that I consider unviable: one in which the individual has no reason to regulate their facial expressiveness. This is not possible, based on BET. As suggested by Alan J. Fridlund from the University of California, Santa Barbara, this assumption is a kind of “shooting oneself in the foot” for the individual who initially proposed the BET, Paul Ekman. When does someone have no reason to hide their facial expression?

In the modern era, it is accepted that culture instills display rules, norms that regulate when, where, what emotion, and with what intensity emotions should be expressed (Friesen, 1972). Ekman himself introduced this idea, which allowed him to explain the results of his studies:

Japanese and Americans differed in their facial expressions, something his universal theory could not account for (Ekman & Friesen, 1969). To the previous proposition of universal facial expression determined biologically, he added cultural influence (Ekman, 1971), giving rise to the neurocultural theory (biology + learning).

The problem is that if we accept Ekman’s ideas about cultural rules, the challenge proposed by the researcher could never be answered without first making some modifications to the theory. In fact, the work of the researcher who issued the challenge is clear evidence of the wide reach of these facial display rules, as he himself asserts that “individuals from all cultures report suppressing their expressions in some contexts, exaggerating them in others, and letting their feelings show as they are in others.” In other words, all people in all cultures regulate their facial expressiveness in one way or another.

So when do we not regulate facial expression?

Original images from studies with nursing students watching videos alone and in the presence of a researcher

Ekman’s original argument (Ekman, 1977, p. 328) is that display rules can be so deeply ingrained in people that they function even when the individual is in complete solitude. So, even in the absence of others, there can be reasons to regulate expression. If we accept this premise, there is no possible situation in which it can be demonstrated that there are no reasons to regulate expression, making it impossible to fulfill the second point of the challenge. It’s a dead alley.

Perhaps we should ask ourselves: Is there a situation in which a person has no reason to regulate their facial expressiveness? That’s a tough question, and I’m not aware of any study that has addressed it, but it would be interesting.

In my opinion, we have to start from the premise that all human behavior is mediated by an unquantifiable multitude of variables and influencing factors that exert their conditioning from distal to proximal to the point where it is impossible to study pure human behavior. Such purity doesn’t exist.

Why would a researcher issue a scientific challenge that 1) cannot be answered and 2) based on the evidence, the results would provide a refutation rather than confirmation of their theory? I don’t know.

5. Polarization in research

I often find myself surprised by unequivocal statements about facial expression, especially when it comes to asserting a theory. Scientific statements defending certain ideas or theories are typically accompanied by qualifiers. Einstein introduced the idea that light is composed of photons with “it seems to me,” and Darwin provided the mechanism of evolution with “I believe.” I’m used to reading this kind of language in scientific discourse.

Apparently, the current global discussion in this subfield of nonverbal communication is limited to debating whether a particular theory is true or false. It’s become a tribe of sports follower that support one team over the other in ways that only allow results to show a winner or loser, rather than growth for the whole sport.

For instance, each researcher in their article tend to respond to the arguments in favor of their theory as they see fit. However, in my opinion, it often seems that the questions posed by their opponents are not being adequately addressed. Maybe some questions cannot be answer with the content we have at the moment.

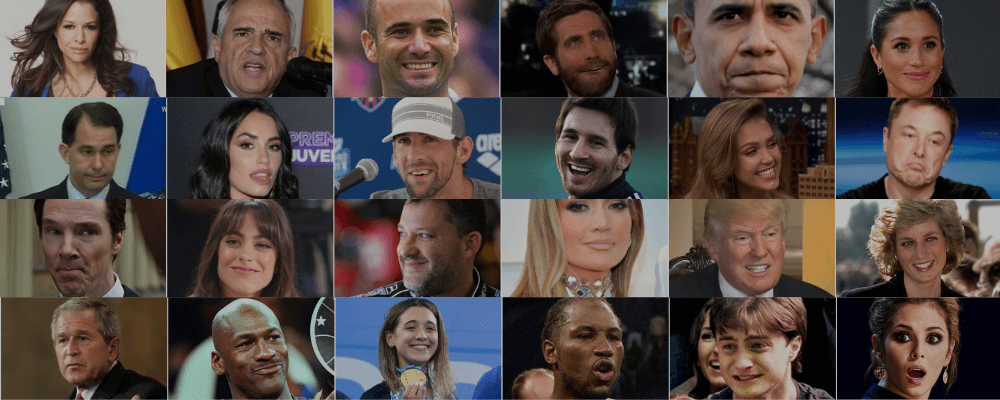

In the realm of public communication, you can see ‘experts’ on social media proclaiming that facial expressions are frequently used as if they were digital scales that precisely indicate not body weight but the emotional state of the analyzed public figures.

But, hey. Wait a minute. Are muscle movements really reliable? Can you use someone’s face to judge their credibility in the same way you measure the temperature in a room? Do you believe it’s easy to diagnose the emotional state of a stranger based solely on their facial expressions? Can you read lies with this technique?

Today, ideological polarization reigns in virtually every domain. While in politics, there is a debate between left and right, in research, the debate revolves around whether facial expression indicates a “basic emotion” or a “social message.” It’s suggested that facial movements signify one or the other. This dichotomy, unfortunately, overlooks the discussion about complexity, variability, ambiguity, combination, sequentiality, and dynamics. Between the two, I lean more towards the social paradigm over the emotional one, but not without recognizing the multitude of messages and signals that the face can convey beyond that single category.

In the same vein, reducing the debate as pro or against Paul Ekman or Lisa Feldman-Barrett is no more useful that reducing the amount of car brands to two. Do the evidence support one as better over the other? both could work well depending on the context? neither? Aren’t there other options or theories? Yes, there are.

I wonder if this binary debate is the best we can do. What do you think?

Some might think, as I have read, that when an unkown (like me) criticizes or contradicts the work of Paul Ekman or a scientific authority, they are only trying to become famous. This ad hominem fallacy only muddies the discussion since this article, like many others, judges empirical results and the associated theories rather than their proponents. It’s easier to kill the messenger than to clean up this mess.

The most curious thing is that the debate sometimes does not seem to delve deeply into what the evidence reveals. Keltner and Cordaro have adapted BET through the new lens of the “Social-Functional Theory.” This theory can be understood as a nuanced, less linear, more flexible and variable perspective, but it still remains, in the words of Fridlund, a new bottling for an old wine of the original theory (2022). It continues to be, in essence, the same simplified proposal that the face primarily communicates emotions and that each of the expressions manifests stereotypical meanings implying that the context has relatively less value than recognized by other theorists (Aviezer et al., 2017).

It’s not just that there are only two theories about what the face communicates. Over the years, researchers like James Russell, Klaus Scherer, Lisa Feldman Barrett, Andrea Scarantino, and Trip Glazer, among many others, have proposed their own alternative conceptions, supported by empirical evidence. However, the debate has become somewhat stagnant, in part, due to the excessive emphasis placed on emotions.

Regarding the current state of knowledge about facial movements, I resonate with the conclusion published by Barrett and colleagues in 2019. The text is a comprehensive analysis and critique of emotional theories of facial expression. One of the conclusions, which I wholeheartedly agree with, is, “The scientific path begins with the explicit recognition that we know much less about emotional expression and perception than we thought” (p. 51).

In that article, they emphasize the growing body of evidence that strongly indicates that there is still much to learn about facial movements. More than four years have passed, and I have not come across a single direct response to that article from the universalists. It’s not that there haven’t been theoretical articles on facial expression, it’s that this particular article did not receive a response to continue the debate. Instead, some have chosen to demonstrate the advancements of their theory (Cowen & Keltner, 2020; Keltner et al., 2022).

So, what now?

Something similar happened with the wonderful text “Inside-Out” by Carlos Crivelli and Alan Fridlund (2019). In this text, the authors outlined more than 19 specific criticisms of the BET theory.

In my opinion, the articles claiming to respond to the two previous publications present powerful arguments, but they do not answer the initial questions that were posed to them. It’s like your automatic email response; it sends what you want to say, but it does not consider the meaning of the message received. In the same way, unviersalists present relevant evidence that, while important, does not suffice to settle the discussion or progress the discussion with a walkable bridge.

6. Why does one theory prevail over the others?

There are several reasons that justify why BET is the dominant “religion” of facial expression. The theory has reigned psychology like an Roman emperor, with total control over any other alternative. Here, I only intend to illustrate the issue, as I am far from proposing a solution to this mystery that no one has managed to solve.

I will now present to you the blueprints of the arquitectural (shacky) foundations that contribute to the favored reverence of BET church, both in popular and scientific contexts.

The five reasons that seem to support the longevity of Basic Emotion Theory (BET) despite the evidence against it

6.1 Tradition: Hundreds of scientific studies conducted over decades, using – quesitonable – methodologies (see Russell, 1994), have provided a coherent theoretical framework for what basic emotions are, why they evolved, and how they are expressed facially.

The impressive degree of consensus across different cultures, at least 21 in the 20th century (Ekman, 2017), has been considered proof of universality. Only when its methodological shortcomings were questioned did academic consensus gradually decline. At the same time, the demonstrations that these expressions are infrequent in naturalistic studies were unexpected for those accustomed to studying them in photographs and manuals.

Over the years, certain evidence has been chosen for convenience while disregarding contradictory results, thus reinforcing the universal and hegemonic paradigm. While it’s true that there is much supporting evidence, there are also several valid criticisms. On more than one occasion (see Fridlund, 1992), BET theorists have readjusted their theoretical model to address some of the contradictions. This doesn’t suggest bad faith or manipulation; instead, it’s a necessary practice for scientific theories to adapt to new evidence. If the car doesn’t work, take it to the mechanic. However, for the discerning and trained eye, the obvious argumentative cracks under the hood continue to exist and have never been fully resolved. Maybe it’s better to manufacture a new car, meaning starting over with a new design based on the evidence rather than on preconceptions from the 20th century.

As the years have passed, even psychology textbooks have accepted the validity of this theory without question. The legitimacy of BET church has remained publicly unchallenge for too long. Although it is gradually losing acolytes, today, police officers, lawyers, psychologists, and social workers are indoctrinated in BET as an unquestionable truth. Based on the scientific results, this seems to pose a risk that people are largely unaware of regarding its short-term, medium-term, and long-term effects. I am certain that the negative consequences will become evident over time. It’s not just an academic discussion, it’s daily life implications are already there.

6.2 Authority: Robert Cialdini, the international authority on persuasion, proposes seven universal principles of influence (1984/2021). One of them is the principle of authority. Cialdini says, “Information from a recognized authority is sometimes a valuable shortcut to deciding how to act in a particular situation” (p. 239). Here, I will explain why I believe this principle has favored the acceptance of BET among followers.

The BET theory is not just one theory among many. The original author, Ekman, besides having a television series inspired by his work (Lie to Me), is considered one of the 100 most important psychologists of the 20th century. He published books with the Dalai Lama and served as a scientific advisor to Pixar for the award-winning movie “Inside Out.” After Darwin, his name is the most frequently mentioned in non-verbal communication texts. In fact, he is the researcher with the most articles as the first or last author among the top 1000 most cited in this field (Plusquellec & Denault, 2018). It is clear that his work not only influenced but also led the field of Nonverbal Communication for nearly five decades. When you have a megaphone, your ideas will spread further and faster than just with your voice.

In contrast, authors of alternative theories seldom appear sporadically on podcasts or in non-traditional media. Their communications are predominantly limited to conferences and academic texts. This glaring difference is a factor that contributes in one way or another to the continued overshadowing of alternative theories by the success of BET. In this respect, it’s up to researchers that have the responsability to speak out publicly about this longstanding unresolved debate. If the lay audience only hears one side of the argument, persuasion results are predictable.

In the words of Dan Ariely¹, a pioneer and authority in the field of behavioral economics: “In the absence of perfect experience or information, we look for social signals that help us determine how impressed we are, or should be, and our expectations take care of the rest” (2008, p. 222). This is the powerful effect of credentials, titles, positions, and all displays of hierarchy. We are highly susceptible hierarchical animals to signals of power, status, and dominance, even if the reader is not consciously aware of it. “If X said it, well, it must be true, isn’t it?”. There are no gods in nonverbal communication, and if there were one, it’s Desmond Morris.

Some of the commercial emotion facial expression ‘recognition’ software

6.3 Business: Providing training to public and private organizations is profitable for those who benefit from it. I, myself, devoted a percentage of my time to such training. For those who simultaneously act as trainers and researchers, there may be a slight conflict of interest in seeing the content they teach validated. Numerous professional training programs for social and Nonverbal Communication skills exist today and constitute an economic market, thus providing a powerful reason to continue with a theory despite its weaknesses. This is especially true when it comes to automating processes and computer vision.

The most obvious case is that of commercial software programs for the “automatic recognition of emotional facial expressions.” These are technological programs that extract and interpret facial movements in emotional terms from videos. Today, they represent a $17 billion market (Crawford, 2021). It’s worth noting that approximately 90% of them are based on the BET theory (approximately, it’s difficult to know for sure). A whole industry supporting on top of an unstable foundation. What could go wrong?

I wonder, what would happen if it were demonstrated that all their efforts and investments had been partially in vain? Crawford essentially concludes that these ’emotion detection’ systems generally do not do what they claim to do. Researchers specializing in the topic offer similar conclusions about the BET theory applied to these software systems: “the theory is) completely outdated” (Gunes and Hung, 2016). I agree.

A paradigmatic case stands out among the rest: the SPOT security program in the U.S.

implemented in more than 160 airports (Denault et al., 2020). This will be a case study in the history of behavior analysis. More than $1.5 billion were invested in training and applying knowledge about nonverbal behavior, including training in Microexpressions of emotions. The figures reported to the U.S. Congress were overwhelming. With disappointing results and more failures than successes, the program received strong criticism. With the evidence on the table, it was decided to discontinue this security protocol. Why? The reasons are multiple and include a lack of results and also the questionable effectiveness of the criteria used. I do not intend to discredit a theory solely for this reason, but I believe it should be questioned, at least.

6.4 Simplicity: The theory is easy and simple to understand. The model proposed by BET can be criticized for being presented as romantic, simple, and reductionist (Crivelli & Fridlund, 2019). With a set of limited criteria and six/seven prototypical expressive faces, it is possible to “train” hundreds of individuals, including law enforcement officers, in recognizing these signals in just a few hours. With this, the theory not only becomes practical but also profitable, as explained above. The central argument of this point is its simplicity. Anyone can understand it, and prior knowledge of psychology, neuroscience, or anthropology is not required.

Series, TV and cinema frequently exhibit exaggerated stereotypes of supposed human facial expressions of emotions, but in everyday life these expressions are infrequent and much more ambiguous.

6.5 Common Sense/Intuition: It appeals to the everyday sensation of believing that we can read the minds of others based on their actions and movements. This is easily reflected in the human tendency to count the successes and ignore the failures. It can be confirmed that “my boss was terrified, and his face revealed it with the position of his eyebrows.” These observations align with what is seen on Netflix and in the movies. The faces of TV characters blatantly reveal their inner states, and the enacted emotions are readily identified. These expressions are acted and exaggerated; therefore, it should be quite obvious to the viewer that they deviate from the natural movements of facial expressiveness. But do we realize it? Do we recognize the difference between natural facial expression and the cinematic one?

Perhaps intuition is not the best strategy for understanding facial expression. Let’s consider the case of the tides. Most people are aware that the tide “rises” and “falls,” right? This can be verified over and over again by visiting a beach. However, that’s not what actually happens. In reality, Neil deGrasse Tyson explains, the gravitational forces of the sun and the moon create bulges of water. So, the Earth rotates in and out of these bulges, which to the human eye looks like the sea level is rising and falling. Similarly, faces can occasionally be accurate thermometers of people’s internal states, but do we understand how they work?

Just like with the tides, we use these ideas daily, but no matter how intuitive they seem, we may not necessarily comprehend them. Seeing a phenomenon is not equivalent to understanding it. The unviersalist theory appeals to intuition, and its simplicity thus facilitates its rapid dissemination and acceptance among the public. In the words of Lisa Feldman Barrett: “The classic view of emotion remains convincing, despite the evidence against it, precisely because it is intuitive” (2017, p. xiii).

7. The Five Reasons and Their Social Consequences:

So, the spread of BET across various disciplines and professional applications has at least five core causes. BET is resorted to: 1) out of tradition and habit, 2) based on the principle of authority, 3) for business purposes, 4) due to its simplicity, and 5) because it is intuitive. However, should we

trust it?

For readers not familiar with Nonverbal Communication, it may seem implausible that BET has a significant impact on you life. However, if you’ve made it this far, it’s likely that you’re passionate about the topic. At first glance, it’s challenging to imagine how this theory about facial expressiveness affects the everyday life of the average citizen, but you can imagine it now. Let’s try to make it more concrete. Think of a member of a jury trial observing (supposed) facial movements of contempt during the examination of witnesses. Based on this, they assume the person is experiencing “duping delight,” the emotion of feeling happy or taking pleasure in

deceiving someone. They negatively color the person’s statement and doubt the witness. Such a decision can impact not only the severity of the sentence but also the outcome of the trial.

However, such facial movements can also appear on the face of a person who feels frustrated, remorseful, superior to the attorney questioning them, proud of themselves, disapproves of someone’s presence in the room, or is dissatisfied with their initial statements. Will the real manual for interpreting facial moments please stand up? Heads up, there’s none.

Now, let’s extrapolate the above case to HR and job interviews, think of it in terms of police or detectives, as well as doctors and psychologists. The consequences become exponential. Some contexts are riskier than others, but in all cases, there is the possibility that the use of BET as scientific justification may negatively impact people. I believe we should start by protecting higher-risk or socially impactful contexts from access to theories and claims from the field of Nonverbal Communication. What I want most is for people to stop accepting, without questioning, a theory that clearly shows shortcomings. Don’t pray without questioning your religion of facial expressions. It might be easier to believe in it because it “solves” the difficult task of interpreting what people feel, but it’s a matter of accepting that this might not be the best option. It may bring you certainty, but I think the captain of the Titanic also thought the ship was unsinkable.

I know that doubting the existence of God causes a lot of discomfort. Changing religions shakes the most deeply rooted foundations of one’s personality, especially if your identity is tied to those beliefs. Moving away from BET will bring many doubts. You will wonder if you are doing the right thing. It will be difficult for you to attribute emotional states to others when it used to be a matter of recognizing the position of their eyebrows or mouth. The important thing, I believe, is for you to evaluate the evidence yourself. Examine each argument up close, read and listen to those who are in favor and against, and only then decide which ideas to accept. Maybe you can save some thousands of dollars in the way.

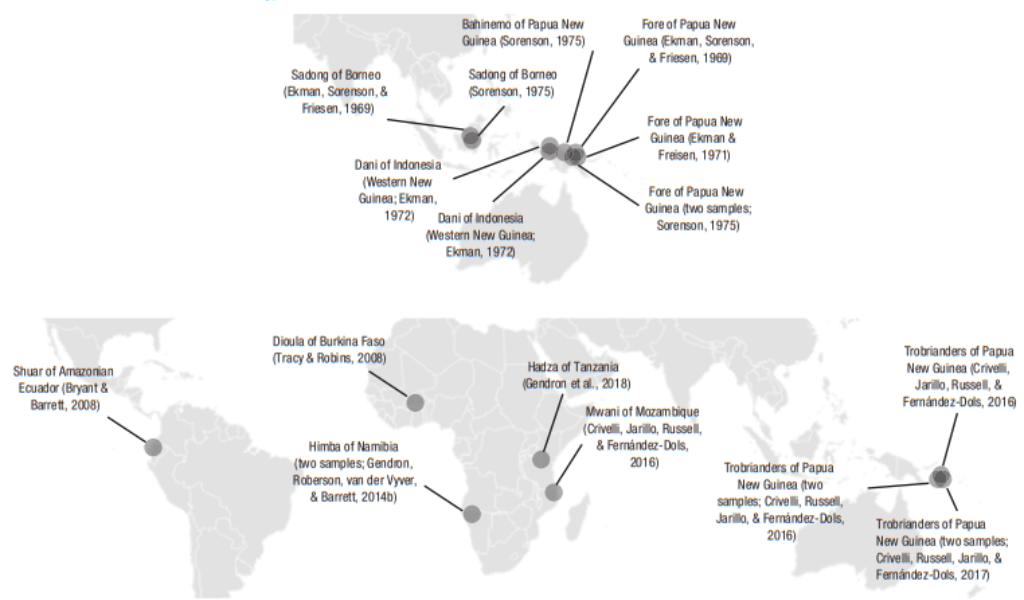

Evidence in the XXI Century

At the end of the 60s, the first cross-cultural studies were carried out with preliterate tribes testing the universality of facial expression. Let’s be clear, from 1976 to 2008 there were no studies with small societies (Gendron et al., 2018). It is a little surprising that only in the 21st century were replication studies carried out again, which are those that try to repeat the study to corroborate the results (this is a problem of science in general: see Chamber, 2017). The big difference is that the new studies incorporated more rigorous methods and discarded many assumptions. What did they discover?

The new results have cast doubt on the acclaimed accuracy of BET. Universality received support ranging from weak to moderate (Barrett et al., 2020). However, studies that contradict the hegemonic BET theory, as well as new findings from studies involving tribes like the Himba or Hazda, rarely receive enough attention (e.g., Gendron et al., 2020). Again, megaphone access makes a difference. Nevertheless, these results alone are insufficient to counteract all the accumulated evidence in favor of BET, although they contribute to well-founded criticisms that are waiting to be addressed in a constructive debate.

A viable explanation for why new data corrects 20th-century knowledge is that a scientific culture was unintentionally created that disregarded discoveries. Instead of using open-response methodologies or naturalistic studies that challenged the foundations of the BET, pre-existing Western categories about how the face should look for a particular emotion were used.

Over time, researchers from fields like psychology, behavioral economics, and marketing applied the BET model to their studies. They continue to do so. Many have accepted as the ‘revealed truth’ that the face has seven stereotypical expressions, each of them an irrefutable vehicle of discrete emotion. So, they unknowingly repeat the sermon, in my opinion, of a theory with fragile support. It seems more a matter of faith than science when it comes to bold statements. Saying BET is universally precise is like insisting everyone loves pineapple on pizza, an obvious non-consensus claim (I can’t stand it).

I believe that the field may be failing at generating new answers to the age-old question: What does facial expression communicate, and what is the relationship between facial expression and internal states? Instead, it seems that they are pursuing evidence that supports one position or another. Trying to find the appropriate solution by cheering one religion over another while ignoring disproving evidence is no more helpful than manually separating waste only to throw it all together in the same dumpster.

Most of the faithful underestimate the evidence that contradicts the BET theory and overestimate the evidence that confirms it. Instead of looking for holes in their own ideas or wondering if they are asking the right question, they assume that the answer is already given – even as the contrary evidence piles up.

9. Current considerations

When perusing the scientific literature on facial expression, many might be surprised. It can be asserted that what the face communicates is entirely secondary to the emotional aspect, within a more comprehensive, realistic, and complex framework of Nonverbal Communication.

Beyond the boundaries of the classical basic emotions, there exists an extraordinarily rich and varied body of knowledge. Studies refer to facial movements in situations of stress and anxiety (Harrigan & O’Connell, 1996; Kraft & Pressman, 2012), facial expressions of pain (Kunz et al., 2019), expressions linked to turn-taking in dialogue when speaking and listening (Bavelas & Chovil, 2018; Heylen et al., 2007), cognitive states (Bitti, 2014), facial displays in situations of personal space invasion (Aranguren, 2015), in bullfighters (García-Higuera et al., 2015), gestures of pleasure and orgasm (Chen et al., 2018), and more. The above list is just a portion of the entire existing universe. What if we have treated emotions as the only planet but it’s just another one in a larger solar system?

Aren’t we missing something if we get bogged down in the seven basic emotions?

Some facial displays from the enormous variety possible

I wonder:

• Why do ‘only’ basic emotions matter so much?

• Why do we settle for just the tip of the iceberg?

• Why do we believe that these facial expressions of emotions are more important than all the others?

• Are they really more frequent than other expressions?

• Is emotional expression stereotyped rather than varied and flexible?

• Can we reliably diagnose what others are feeling solely based on facial movements?

• If we can recognize emotions in others from their faces, what is the accuracy rate?

• With what degree of certainty do we know whether someone’s emotional expression is

genuine or fake?

Given the current evidence, filled with contradictions, results for and against, 1) wouldn’t it be appropriate to say that ‘it seems to me that facial expression reveals basic emotions with prototypical expressions universally’, and 2) why should the burden of proof be on those who disagree?

I understand that there are literally hundreds of studies supporting the veracity of BET, and for this reason, they defend its scientific status. But there are also dozens of articles, discoveries, and valid criticisms inviting us to recalibrate the theory. Some of these criticisms include the use of decontextualized images, the use of photographs instead of videos, actors acting out emotions, overly posed expressions, forced-choice responses, high variability in the expression of the same emotion, lack of uniformity in physiology, among others.

If there is currently contradictory evidence for the arguments presented, both regarding the universality of emotional expressions and facial displays of social messages (arguing that Fridlund’s BECV has not yet managed to explain the high level of cross-cultural agreement in the perception of emotions and the consistency in the production of such expressions), the most reasonable approach would be to present studies that resolve these inconsistencies. There’s more data than answers, more unanswered questions than certainties. Criticisms from one side to the other, and few direct responses to the counterpart, although the conversation exists. And collaborative work? Is this still beyond the realm of possibility, or not?

Since we’re extending an invitation to facial expression researchers, why not think about

creating studies that would satisfy opposing theorists? It would be progress if we could create instances for researchers to agree on the methodology of a particular study beforehand. This would offer many opportunities and truly advance facial expression research. Today, knowledge seems to be at a standstill. It’s hard to answer the question of what the face communicates not due to a lack of information, but probably due to an excess of it. This is to me a crucial truth.

10. Conclusion

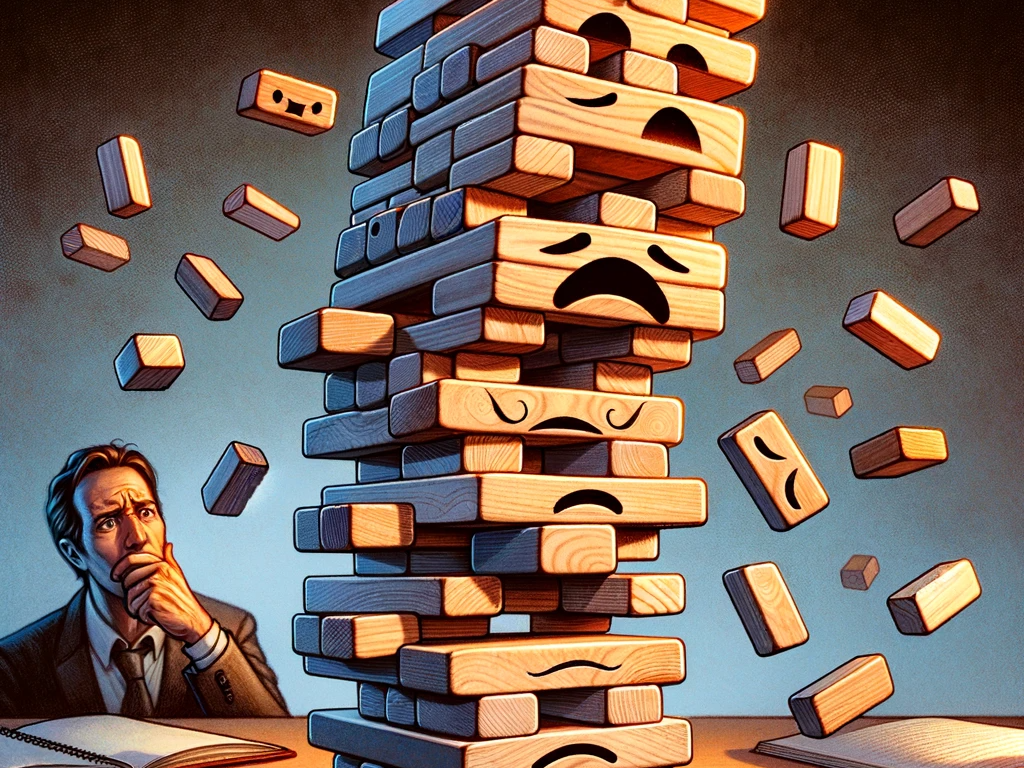

In my view, BET proponents have constructed a Jenga tower based on their studies. The problem lies in one crucial detail: the tower of blocks is in freefall. However, it has not collapsed yet because there are a set of hands (the 5 reasons presented above) preventing its imminent fall. Those who defend BET (I believe) are not consciously aware that the Jenga can no longer stand on its own, and it’s just a matter of time before it falls, and the ‘game’ ends. Researchers who patch the theory only prolong the inevitable: we need new ideas, theories, and research. Some buildings need to implode leaving path to more modern architecture

La metáfora del jenga que permite explicar simplificadamente el estado actual del debate con respecto a los postulados originales de BET

Very few are willing to do what etically admirable Joseph Ledoux did in the field of neuroscience: retract and acknowledge evidence that contradicts their own work. Researcher James Russell, the author of the dimensional theory of emotions, believed that valence of facial expression, that is, its positive or negative nature, mattered more than the context when inferring what someone feels. He confesses, “I was wrong: context trumps valence judgments” (2017, p. 97). Bravo.

I know and respect the scientific work of Paul Ekman and other adherents of the BET. However, I believe the phrase “Their faces will move the same. Show me the study in which the emotion is evoked, and that expression does not happen. You won’t find that” is, to say the least, tendentious. I cannot take that seriously. Should we? Possibly, this decorated researcher, being part of a podcast, made the statement without being aware of the general implications or the extent of his argument. He was trying to explain the literature on facial expressions, and it’s possible he also expressed his opinion by pushing the findings beyond what is empirically demonstrable. Let’s grant him that.

Current evidence refutes the idea that if one intensely experiences a specific emotion and has no reason to regulate expressiveness, all people in the world will display the same facial expression. It seems quite clear to me that facial movements are a bit more complex than a simple automatic reflection of one’s internal state. Thats what ethologists thought about fixed action patterns in the fiftees. We already know this.

This does not negate the existence of a kernel of truth in the universality of facial expressiveness. We all have the same cutaneous muscles (although this varies among some human races) and, therefore, are potentially capable of making the same facial movements. We also share an evolutionary heritage. In fact, it’s difficult to completely refute the high cross-cultural consensus in recognizing certain stereotypical facial expressions. However, the frequency, form, intensity, and appearance of natural facial expressions are far from how this theory is currently being applied, which intrudes into the doctor-patient relationship and even reaches the courts in the form of expert testimony.

I would say to be careful of self-announced preachers of the word of gospel regarding their superhuman skills of reading human emotions in flashes in the face, since in the same way, you shouldn’t trust the predictions of an astrologer. This approach is most often taken by some practitioners and very rarely by researchers.

Just to be clear, I don’t intend to discard emotional facial expressions and start from scratch. Instead, I’m trying to demonstrate that the theory and practice of these assumptions are far removed from facial expressivity in everyday life. If you keep looking in your bedroom for the keys you lost at the mall, you will never find them. Applying this theory without understanding all these limitations and contradictions might make you feel confident, but you’ll have to accept that it’s partially an illusion. Using a broken compass won’t take you to your destination.

I argue that the scientific discussion should aim to explain 1) why there is moderate agreement across cultures for facial expressions and also 2) investigate whether such facial manifestations are indeed externalizations of universal discrete emotions or if there is an uncharted territory of what the face can communicate with its transitory movements. Declaring that the code of the face has been solved equates to climbing to 2000 meters of the Everest and proclaiming you reached the top.

Photograph of the participants of the historic debate, which sets an excellent precedent for the future

The radical assumption that “the face will move the same in everyone,” which cannot be supported by any specific scientific study (as I explained above), has already been questioned by more than one study (at least four). I don’t intend to enter the debate because the format of this article doesn’t allow it, although I’d love to promote it. We need it. I’d like to see more interactions between intellectual opponents who are ultimately research colleagues. I applaud the debate between Dacher Keltner and Daniel Cordaro on one side and Alan Fridlund and James Russell on the other, moderated by Andrea Scarantino (2016).

Going back to the comment that ignited my desire to answer the challenge, I believe it’s worth noting that in the same interview, the researcher, despite his theory being contradicted, acknowledges the validity of data from some opponents such as Feldman Barrett. However, he didn’t agree with the interpretations made of such results. This, I think, is an excellent step in the direction researchers should move in: one where common ground can be established, and disagreements can be discussed. To add to this, and I greatly appreciate this, is that “people… argue against each other, and I think that’s not a constructive approach because we have been doing it for 50 years or more, just pointing fingers at each other. We need to get away from pointing fingers at each other.” I completely agree, but there are better ways than proposing an untestable challenge.

Therefore, in this article, I intend to: 1) point out the shortcomings of BET, 2) respond to the challenge, 3) highlight the contradictions in facial expression research, 4) encourage

collaborations between intellectual opponents, and 5) progress towards a more complex dissemination and application of knowledge related to facial expressivity.

Ultimately, I believe we still don’t understand facial expression, nor do we have robust evidence of the relationship between facial movements and emotions. Recognizing the threshold between knowledge and ignorance, it’s vital to initiate new research. Under the false security of BET as the superior explanation, research may be lacking opportunities for new ideas and experiments.

Anyone who claims to completely understand the complexity of the face is probably confused or unaware of the overwhelming amount of information in the existing body of knowledge. Or maybe the ignorant one is me. You decide.

At the moment, we lack a general theory of facial expressivity, a theoretical model explaining how every internal state or social message is expressed. The search for explanations is just beginning because old assumptions are collapsing with current evidence. We must first recognize our own ignorance to start asking the right questions. To do so, “We need to expand our research by disentangling emotion and facial behavior” (Durán & Fern, 2021, p. 35). Only then can we have a better understanding of facial expressivity in the future.

I wish for one thing in particular: that we steer the future of facial expression study and understanding in a realistic way, synthesizing the current body of knowledge. Let’s unite 20th-century evidence with 21st-century evidence. Let’s stop defending theories just for the sake of defending them. The evidence is clear: we still don’t understand facial expression. No one does. No one has the magic formula to read emotions or identify people’s secret thoughts.

Stop making us believe that we understand it completely. Let’s try to comprehend facial expressivity in its full extent as it is, rather than as we wish it to be. The consequences of refusing to accept this complexity can be devastating. So, are we ready to topple the sacred cow of BET, or will we continue to worship at the altar of outdated science?

References:

Aranguren, M. (2015). Nonverbal interaction patterns in the Delhi Metro: Interrogative looks and play-faces in the management of interpersonal distance. Interaction Studies, 16(3), 526-552.

Ariely, D., & Jones, S. (2008). Predictably irrational (pp. 278-9). New York: HarperCollins.

Aviezer, H., Ensenberg, N., & Hassin, R. R. (2017). The inherently contextualized nature of facial emotion perception. Current opinion in psychology, 17, 47-54.

Aviezer, H., Trope, Y., & Todorov, A. (2012). Body cues, not facial expressions, discriminate between intense positive and negative emotions. Science, 338(6111), 1225-1229.

Barrett, L. F. (2017). How emotions are made: The secret life of the brain. Pan Macmillan.

Barrett, L. F., Adolphs, R., Marsella, S., Martinez, A. M., & Pollak, S. D. (2019). Emotional expressions reconsidered: Challenges to inferring emotion from human facial movements. Psychological science in the public interest, 20(1), 1-68.

Bavelas, J., & Chovil, N. (2018). Some pragmatic functions of conversational facial gestures. Gesture, 17(1), 98-127.

Bitti, P. E. R., Bonfiglioli, L., Melani, P., Caterina, R., & Garotti, P. (2014). Expression and communication of doubt/uncertainty through facial expression. Ricerche di Pedagogia e Didattica. Journal of Theories and Research in Education, 9(1), 159-177.

Camras, L. A., & Shutter, J. M. (2010). Emotional facial expressions in infancy. Emotion review, 2(2), 120-129.

Camras, L. A., Castro, V. L., Halberstadt, A. G., & Shuster, M. M. (2017). Spontaneously produced facial expressions in infants and children. In (Eds.) Fernández- Dols & Russell, The science of facial expression (pp. 279-296).

Chambers, C. (2017). The seven deadly sins of psychology. In The Seven Deadly Sins of Psychology. Princeton University Press.

Chen, C., Crivelli, C., Garrod, O. G., Schyns, P. G., Fernández-Dols, J. M., & Jack, R. E. (2018). Distinct facial expressions represent pain and pleasure across cultures. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(43), E10013-E10021.

Cialdini, R. B. (2003). Influence. Influence At Work.

Cowen, A. S., & Keltner, D. (2020). What the face displays: Mapping 28 emotions conveyed by naturalistic expression. American Psychologist, 75(3), 349.

Crawford, K. (2021). The atlas of AI: Power, politics, and the planetary costs of artificial intelligence. Yale University Press.

Crivelli, C., & Fridlund, A. J. (2019). Inside-out: From basic emotions theory to the behavioral ecology view. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 43(2), 161-194.

Denault, V., Plusquellec, P., Jupe, L. M., St-Yves, M., Dunbar, N. E., Hartwig, M., … & Van Koppen, P. J. (2020). The analysis of nonverbal communication: The dangers of pseudoscience in security and justice contexts. Anuario de Psicología Jurídica.

Durán, J. I., & Fernández-Dols, J. M. (2021). Do emotions result in their predicted facial expressions? A meta-analysis of studies on the co-occurrence of expression and emotion. Emotion, 21(7), 1550.

Durán, J. I., Reisenzein, R., Fernández-Dols, J. M., & Russell, J. A. (2017). The science of facial expression.

Ekman, P., & Friesen, W. V. (1969). The repertoire of nonverbal behavior: Categories, origins, usage, and coding. semiotica, 1(1), 49-98.

Ekman, P. (2017). Facial Expressions. In (Eds.). Dols, J. M. F., & Russell, J. A. (2017). The science of facial expression. Oxford University Press (pp. 39-56)

Fernández-Dols, J. M., Carrera, P., & Crivelli, C. (2011). Facial behavior while experiencing sexual excitement. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 35(1), 63-71.

Fridlund, A. J. (1992). Darwin’s anti-Darwinism in the” Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals.”.

Fridlund, A. J. (2022). Demons of Emotion. Evolutionary Studies in Imaginative Culture, 6(1), 25-28.

Galati, D., Sini, B., Schmidt, S., & Tinti, C. (2003). Spontaneous facial expressions in congenitally blind and sighted children aged 8–11. Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness, 97(7), 418-428.

García-Higuera, J. A., Crivelli, C., & Fernández-Dols, J. M. (2015). Facial expressions during an extremely intense emotional situation: Toreros’ lip funnel. Social Science Information, 54(4), 439-454.

Gaspar, A., Esteves, F., & Arriaga, P. (2014). On prototypical facial expressions versus variation in facial behavior: What have we learned on the “visibility” of emotions from measuring facial actions in humans and apes. The evolution of social communication in primates: A multidisciplinary approach, 101-126.

Gendron, M., Crivelli, C., & Barrett, L. F. (2018). Universality reconsidered: Diversity in making meaning of facial expressions. Current directions in psychological science, 27(4), 211-219.

Gendron, M., Hoemann, K., Crittenden, A. N., Mangola, S. M., Ruark, G. A., & Barrett, L. F. (2020). Emotion perception in Hadza hunter-gatherers. Scientific reports, 10(1), 3867.

Friesen, W. V. (1972). Cultural differences in facial expressions in a social situation: An experimental test of the concept of display rules. University of California, San Francisco.

Gendron, M., & Barrett, L. F. (2017). Facing the past: a history of the face in psychological research on emotion perception. In The science of facial expression (pp. 15-38).

Gunes, H., & Hung, H. (2016). Is automatic facial expression recognition of emotions coming to a dead end? The rise of the new kids on the block. Image Vision Comput., 55, 6-8.

Harrigan, J. A., & O’Connell, D. M. (1996). How do you look when feeling anxious? Facial displays of anxiety. Personality and individual differences, 21(2), 205-212.

Harris, C., & Alvarado, N. (2005). Facial expressions, smile types, and self-report during humour, tickle, and pain. Cognition & Emotion, 19(5), 655-669.

Heylen, D., Bevacqua, E., Tellier, M., & Pelachaud, C. (2007). Searching for prototypical facial feedback signals. In Intelligent Virtual Agents: 7th International Conference, IVA 2007 Paris, France, September 17-19, 2007 Proceedings 7 (pp. 147-153). Springer Berlin Heidelberg.

Horstmann, G. (2003). What do facial expressions convey: Feeling states, behavioral intentions, or actions requests?. Emotion, 3(2), 150.

Keating, C. F. (2016). The life and times of nonverbal communication theory and research: Past, present, future. In APA handbook of nonverbal communication. (pp. 17-42). American Psychological Association.

Keltner, D., Sauter, D., Tracy, J., & Cowen, A. (2019). Emotional expression: Advances in basic emotion theory. Journal of nonverbal behavior, 43, 133-160.

Keltner, D., Sauter, D., Tracy, J. L., Wetchler, E., & Cowen, A. S. (2022). How emotions, relationships, and culture constitute each other: Advances in social functionalist theory. Cognition & Emotion, 36(3), 388-401.

Kraft, T. L., & Pressman, S. D. (2012). Grin and bear it: The influence of manipulated facial expression on the stress response. Psychological science, 23(11), 1372-1378.

Kunz, M., Meixner, D., & Lautenbacher, S. (2019). Facial muscle movements encoding pain—a systematic review. Pain, 160(3), 535-549.

Matsumoto, D., & Hwang, H. C. (2016). The cultural bases of nonverbal communication. In APA handbook of nonverbal communication. (pp. 77-101). American Psychological Association.

Matsumoto, D., Frank, M. G., & Hwang, H. S. (Eds.). (2013). Nonverbal communication: Science and applications. Sage Publications.

Matsumoto, D. E., Hwang, H. C., & Frank, M. G. (2016). APA handbook of nonverbal communication. American Psychological Association.

Plusquellec, P., & Denault, V. (2018). The 1000 most cited papers on visible nonverbal behavior: A bibliometric analysis. Journal of Nonverbal Behavior, 42(3), 347-377.

Reisenzein, R., Bördgen, S., Holtbernd, T., & Matz, D. (2006). Evidence for strong dissociation between emotion and facial displays: the case of surprise. Journal of personality and social psychology, 91(2), 295.

Russell, J. A. (1994). Is there universal recognition of emotion from facial expression? A review of the cross-cultural studies. Psychological bulletin, 115(1), 102.

Schützwohl, A., & Reisenzein, R. (2012). Facial expressions in response to a highly surprising event exceeding the field of vision: a test of Darwin’s theory of surprise. Evolution and Human Behavior, 33(6), 657-664.

Scotto, S. C. (2022). A Pragmatics-First Approach to Faces. Topoi, 41(4), 641-657.

Valente, D., Theurel, A., & Gentaz, E. (2018). The role of visual experience in the production of emotional facial expressions by blind people: A review. Psychonomic bulletin & review, 25(2), 483-497.

Wenzler, S., Levine, S., van Dick, R., Oertel-Knöchel, V., & Aviezer, H. (2016). Beyond pleasure and pain: Facial expression ambiguity in adults and children during intense situations. Emotion, 16(6), 807.

¹Even if his scientific work and credibility is damage, the quote is still true

- Compartir:

También te puede gustar

The Art of Sign Stealing: Nonverbal Communication Lessons from Connor Stalions

- septiembre 2, 2024

- por Alan Crawley

- en Análisis de Caso

Comentarios

Very nice overview of this issue.

However, you are much too kind and reverent toward the well-spring of this “religion.”

While “religion” does scrape at the real skin of this issue, it’s much too gentle.

The Ekman-founded and Ekman-led “all faces, in all places, in all cultures move the same way to reveal the same emotions” belief system is more than a “religion.” If you want to use the religion metaphor, then “cult” is a much better term for it.

Scientists and researchers have very explicitly and publicly branded the Ekman belief system as pseudoscience.

Even more realistic, and more to the point, are “scam” or “con.”

The cult following of BET is a manifestation of the modern-day fallacy of “follow The Science.” Ekman and his followers publish in “peer-reviewed journals.” They have millions of dollars of government funding and support.

Since they are The Science, the settled-Science (since Darwin!), non-followers are minimized, de-platformed, and otherwise rejected.

Another interesting point in this article is quoting two other fabulists: Hariri and Ariely, especially Ariely. He is an almost perfect doppleganger of Ekman. The irony of “lie detection” expert lying; and the “honesty guy” being dishonest is too delicious.

My recent article on Ekman’s pseudoscience, linked below, is an excerpt from my book: Holistic Contextual Credibility Assessment. Which refutes the Ekman claims, and lays out a real-world-proven approach to assessing credibility.

https://kentclizbe.substack.com/p/ekmans-microexpression-pseudoscience

Hi Kent, I very much appreciate your time spent reading and engaging with the article.

Indeed, I read your article and find it a very detailed and well-founded critique of Ekman’s work. The critiques on Microexpressions are very well deserved. Still, I think your stance neglects many of Ekman’s scientific achievements making the debate personal rather than theoretical. Saying that the community regards Ekman as a pseudoscientist is a bold claim, which, from inside academia, I have to deny as a given truth. It’s much more complicated than that.

Regarding the authors cited, you have to know that the quotes are still true, even if you like or dislike those authors. I chose to leave them, even if I disagree with the authors (on some multiple points), since their words are adequate. That’s also a point that I make in this article that I think you disagree with: even if I don’t agree with many of Ekman’s points, we cannot discard everything he has done and we should give him the applause he deserves for some of his work.

Good luck!